January 3 stands out as a symbolic date in the history of twentieth-century Italy, linking together events that at first glance appear unrelated, yet together trace a coherent historical trajectory. On this single day, in different years, Italy experienced the open consolidation of Fascist dictatorship, the birth of public television, and the death of a partisan who embodied armed resistance. In 1925, a parliamentary speech marked the definitive authoritarian turn of the regime; in 1954, regular broadcasting by RAI inaugurated a new era of mass communication; in 1944, Lanciotto Ballerini lost his life while fighting against Nazi occupation and Fascist collaboration. Viewed collectively, these events reflect three fundamental dimensions of modern Italian history: political power, public communication, and civic resistance. The date of 3 January thus becomes a lens through which to observe how authority is imposed, how society is reshaped through media, and how individual choices can challenge oppression and leave a lasting imprint on national memory.

1925 - Benito Mussolini’s Speech and the Dictatorial Turn of the Fascist Regime

The year 1925 marks a decisive turning point in the political history of twentieth-century Italy. It was the moment when Fascism abandoned any remaining ambiguity and openly transformed itself from an authoritarian government operating within a parliamentary framework into a full-scale dictatorship. The symbolic and political culmination of this process was the speech delivered on 3 January 1925 before the Chamber of Deputies by Benito Mussolini. Far from being a defensive address, the speech represented a calculated challenge to Parliament and a public declaration of personal power.

The context surrounding this speech was one of profound political and moral crisis. In June 1924, Italy had been shaken by the abduction and murder of Giacomo Matteotti, a socialist deputy who had courageously denounced electoral fraud, violence, and intimidation carried out by Fascist squads during the general elections. Matteotti’s assassination provoked widespread outrage and cast serious doubt on the legitimacy of Mussolini’s government, both domestically and internationally. For the first time since coming to power in 1922, Mussolini appeared vulnerable.

In the months following the murder, the Fascist regime entered a period of uncertainty. Opposition deputies withdrew from Parliament in what became known as the Aventine Secession, hoping that the King would intervene and dismiss Mussolini. This strategy proved ineffective. The monarch remained passive, and the absence of the opposition from the Chamber weakened parliamentary resistance rather than strengthening it. Mussolini, observing the paralysis of institutions and the lack of decisive action against him, gradually regained confidence and prepared for a decisive confrontation.

The speech of 3 January 1925 was the moment when Mussolini chose to act openly. Standing before a largely submissive Parliament, he abandoned any pretense of conciliation. Instead of denying the violent nature of Fascism, he boldly declared that he assumed “political, moral, and historical responsibility” for what had happened in Italy. This statement has often been misunderstood as a confession. In reality, it was an assertion of authority. Mussolini was not submitting himself to judgment; he was proclaiming that he alone embodied the responsibility of the regime and, by extension, the nation.

At the same time, Mussolini carefully denied being the direct instigator of Matteotti’s murder. This distinction was crucial. By rejecting personal criminal responsibility while embracing an abstract, historical responsibility, he neutralized the possibility of legal prosecution and shifted the debate away from law and justice toward power and destiny. Responsibility, in Mussolini’s rhetoric, was no longer something that limited authority—it was something that legitimized it.

One of the most striking elements of the speech was its openly confrontational tone. Mussolini challenged the Chamber of Deputies to indict him if it believed him guilty. The challenge was purely rhetorical: he knew that Parliament, weakened by fear, internal divisions, and the absence of the opposition, was incapable of acting. This moment symbolized the collapse of parliamentary sovereignty. From that day onward, the legislature ceased to function as a check on executive power and became a ceremonial institution subordinated to the will of the regime.

The consequences of the speech were immediate and far-reaching. In the months that followed, Mussolini initiated a systematic dismantling of the liberal state. A series of laws—later known as the “exceptional Fascist laws”—abolished freedom of the press, dissolved opposition parties, suppressed trade unions, and established strict censorship. Local elected authorities were replaced with officials appointed by the central government, and the police were granted sweeping powers to repress dissent. Italy formally entered the era of one-party rule.

It is important to note that the Fascist dictatorship was not imposed overnight through a single coup. Rather, it emerged through a combination of political violence, institutional weakness, and calculated rhetoric. The speech of January 1925 stands out because it marked the moment when Mussolini publicly acknowledged—and embraced—the authoritarian nature of his rule. What had previously existed behind intimidation and ambiguity was now openly declared from the floor of Parliament itself.

From a historical perspective, this episode illustrates how democratic systems can be undermined from within. The dictatorship was not established by abolishing Parliament outright, but by rendering it powerless. Mussolini’s speech demonstrated how a leader could exploit a national crisis, present himself as the sole guarantor of order, and transform responsibility into a justification for unchecked authority. The failure of institutions to respond decisively played a central role in this process.

In retrospect, the events of 1925 represent the definitive end of Italian liberal democracy. The speech delivered by Mussolini was not merely an oratorical performance; it was a political act that redefined the nature of the state. By openly challenging Parliament and asserting his supremacy over law and institutions, Mussolini laid the ideological and practical foundations of a dictatorship that would dominate Italy for two decades.

The legacy of that moment remains deeply significant. It serves as a reminder that authoritarian regimes often consolidate power not through sudden ruptures, but through deliberate confrontations in which the weakness of democratic institutions is exposed. Mussolini’s speech of 3 January 1925 stands as one of the clearest examples of how rhetoric, intimidation, and institutional failure can converge to bring about the collapse of constitutional government.

1954 -The Beginning of RAI Broadcasting and the Birth of Italian Television

3 January 1954 marks a milestone in the cultural and social history of modern Italy. On this day, the Radiotelevisione Italiana, known as RAI, officially launched its regular television broadcasting service, and the first Italian television news program was aired. This event did not merely introduce a new technology; it signaled the start of a profound transformation in how Italians received information, experienced culture, and perceived their collective national identity.

In the early 1950s, Italy was still emerging from the devastation of the Second World War and the long shadow of Fascist dictatorship. Democratic institutions were fragile, economic conditions remained difficult, and society was deeply fragmented along regional, linguistic, and social lines. Radio had already become an essential means of communication, but television represented something entirely new. By combining sound, moving images, and live reporting, it promised an unprecedented level of immediacy and emotional impact. Television was not simply an evolution of radio; it was a revolution in mass communication.

The choice of 3 January as the official launch date carried symbolic meaning. The beginning of the year suggested renewal, progress, and a forward-looking vision. Television was presented as a public service and a tool for national reconstruction, not merely a form of entertainment. From the outset, RAI was conceived as a central institution of the Italian Republic, tasked with educating citizens, strengthening democratic values, and fostering a shared cultural space across the country.

On the same day broadcasting began, Italy witnessed the first television news bulletin in its history. This moment represented a turning point in the relationship between citizens and information. For the first time, news was no longer confined to newspapers or radio voices; it appeared on screen, embodied by faces, gestures, and visual evidence. Political leaders, public events, and international affairs became visible and tangible. This shift profoundly changed how reality itself was perceived, making information more immediate and emotionally engaging.

The first television news program was characterized by a sober and formal style. There was no emphasis on spectacle or dramatization. This restraint reflected the cautious atmosphere of the time and the desire to establish television as a credible and authoritative source of information. After years of propaganda and censorship under Fascism, rebuilding public trust in media was essential. RAI adopted an institutional tone, presenting itself as a reliable intermediary between the state and the public.

In 1954, television sets were still rare and expensive. Only a small number of households, mostly in large cities, owned one. Nevertheless, the impact of television was immediate. People gathered in bars, cafés, community centers, and in front of shop windows to watch broadcasts together. Television viewing became a collective experience, creating new social rituals and shared moments. Even those who did not own a television felt its influence through these communal gatherings.

One of the most significant consequences of the introduction of television was its role in linguistic and cultural unification. Postwar Italy was a country of dialects; for many citizens, standard Italian was not the language spoken at home. Through news programs and educational broadcasts, television played a crucial role in spreading a common language and shared cultural references. For millions of Italians, television became an informal classroom, teaching not only language but also social norms, behavior, and a sense of belonging to a national community.

The television news program quickly assumed a central place in daily life. It became a fixed appointment, structuring the rhythm of the day and shaping public awareness. By selecting and presenting events, the news did more than inform—it organized reality, defining what mattered and how it should be interpreted. In the context of the Cold War and intense internal political competition, this role was particularly significant. Television became a powerful instrument in shaping public opinion and political consciousness.

As a public broadcaster, RAI operated under strong institutional and political influence. This resulted in certain limitations on editorial freedom, but it also ensured stability and continuity. Television was seen as a tool to guide Italy through modernization, promoting education, civic responsibility, and social cohesion. Over time, RAI expanded its programming to include cultural shows, theater productions, educational courses, music, and the first television series. Yet news broadcasting remained the core of its mission.

The historical importance of 3 January 1954 extends beyond the history of media. It represents Italy’s entry into the age of visual mass communication. Television contributed to shaping the conditions for the economic and social transformation that would culminate in the Italian economic boom of the late 1950s and 1960s. It helped create a shared national narrative in a country long marked by regional diversity and division.

In conclusion, the launch of RAI’s television broadcasts and the airing of the first news program were not merely technical achievements. They marked a defining moment in Italy’s postwar rebirth. Television became both a mirror of society and a force capable of shaping it. The events of 3 January 1954 laid the foundations for a new way of seeing, understanding, and narrating Italy to itself—a transformation whose effects continue to resonate in Italian society to this day.

1944 - Lanciotto Ballerini: life, war, and sacrifice of a Tuscan partisan

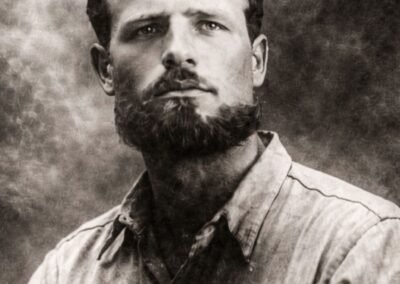

Lanciotto Ballerini

(Campi Bisenzio, 15 August 1911 – Calenzano, 3 January 1944)

Lanciotto Ballerini stands as one of the most significant figures of the Italian Resistance in Tuscany. His biography, reconstructed through local archives, ANPI documentation, and historical memory, traces the complex path of a man who experienced the wars of Fascist Italy as a soldier, rejected ideological conformity, and ultimately chose armed resistance against Nazi occupation and Fascist collaboration—paying for that choice with his life.

Born in Campi Bisenzio on 15 August 1911 into a family of butchers, Ballerini’s early years were far removed from politics. His youth was marked instead by an intense involvement in sport, particularly boxing. In 1929 he achieved notable success, becoming Italian middleweight champion in the primi pugni category. Boxing shaped his character, instilling discipline, physical endurance, and determination—qualities that would later emerge with clarity in both his military conduct and his partisan leadership.

From the early 1930s onward, Ballerini’s life became intertwined with the military ventures of Fascist Italy. In 1935–1936 he took part in the Ethiopian War. During the conflict he distinguished himself through an act of courage that earned him a medal for merit and promotion in rank: he saved the lives of fellow soldiers during an enemy attack. Upon returning to Italy he was celebrated as a hero. Yet it was precisely at this moment that his moral distance from the regime became evident. When offered membership in the National Fascist Party, he refused the party card outright—a gesture that, in the political climate of the time, carried considerable personal risk and revealed a clear rejection of Fascist ideology.

In 1939 Ballerini was recalled to arms for the occupation of Albania. With the outbreak of the Second World War, he was then deployed with Italian occupation forces to Greece and Yugoslavia, where he remained from 1940 to 1943. It was in the Balkans that his break with the Fascist system became definitive. Witnessing the harsh repression inflicted on civilian populations, Ballerini acted in open contrast to the logic of occupation. At night, secretly leaving his camp, he warned villages of impending Italian artillery bombardments, allowing men, women, and children to flee and seek safety. In Yugoslavia he also came into contact with Tito’s partisans, an experience that brought him closer to the concrete reality of liberation struggle and resistance.

In June 1943 Ballerini was repatriated because of severe rheumatic pain caused by the hardships endured at the front. After the armistice of 8 September 1943 and the collapse of the Italian state, the country descended into chaos. Tuscany fell under German occupation and the control of the Italian Social Republic. In this context, Ballerini made a final and decisive choice. In the autumn of 1943 he went to Monte Morello, where he organized and led one of the earliest partisan formations to emerge in the region.

The group he commanded was remarkable for its international composition. Alongside Italian partisans fought volunteers from across Europe: a Scot, a Serb, a Croat, a Ukrainian, and a Russian. This diversity highlighted the broader, transnational character of the anti-Fascist struggle and reflected Ballerini’s authority as a leader capable of uniting men of different backgrounds under a shared cause.

The decisive moment of his partisan career came on 3 January 1944. On that day, the Garibaldi assault formation known as the “Lupi Neri” was positioned near the Case di Valibona, in the Calvana mountains. Following a denunciation, the unit was surrounded by two enemy columns: one consisting of approximately 80 Republican Fascist militiamen supported by the Carabinieri from Prato and Vaiano, the other made up of around 60 members of the Fascist “Muti” formation accompanied by the Carabinieri of Calenzano. The objective was the complete annihilation of the partisan group.

Faced with encirclement, Lanciotto Ballerini chose to engage the enemy in order to allow the bulk of his comrades to break away and escape. He fought with exceptional determination, inflicting heavy losses on the attackers. During the clash he advanced almost alone against enemy positions equipped with three machine guns, using hand grenades in an attempt to neutralize them. It was during this action that he was killed. His sacrifice enabled most of the formation to withdraw and survive.

The same engagement claimed the lives of two of his companions. Luigi Giuseppe Ventroni, a Sardinian machine gunner, was seriously wounded, captured, and burned alive in a fortified hayloft. The Russian partisan Vladimiro Andrey was taken prisoner by Fascist forces and executed on the spot. These deaths marked one of the most tragic episodes of the partisan war in Tuscany.

Ballerini’s death had a profound symbolic impact. It occurred at a time when the Resistance was still paying an extremely high price and the outcome of the war remained uncertain. His sacrifice became a point of reference in the collective memory of the Tuscan Resistance. As early as 1944, the football team of Campi Bisenzio was named in his honor and continues to bear the name Lanciotto Campi Bisenzio today. The town’s stadium is also dedicated to him, as is the Coppa Lanciotto Ballerini, an amateur cycling race held since 1946. In the postwar years, numerous streets, roads, and squares across the Province of Florence were named after him.

In 2011, on the occasion of the centenary of his birth, the Municipality of Campi Bisenzio promoted the creation of the comic book L’eroe partigiano by Jacopo Nesti and Francesco Della Santa, with the active involvement of the local ANPI section named after Lanciotto Ballerini. This initiative helped pass his story on to younger generations, reinforcing his place in local and national historical memory.

The figure of Lanciotto Ballerini embodies the journey of many Italians who, after serving in the wars of Fascist expansion, consciously chose to oppose the regime and the Nazi occupation. His life, ending on 3 January 1944, stands as concrete testimony to the fact that the Italian Resistance was built not only by famous leaders but by ordinary men capable of transforming personal experience into a collective choice for freedom, responsibility, and sacrifice.